Inheritance

This lesson introduces the concept of inheritance in object-oriented programming, which allows creating new classes based on existing classes. It also presents the concept of polymorphism, which enables functions and methods to work with objects of different types in a consistent manner.

Concept of inheritance

Let's consider that in our program we have a class to represent animals:

class Animal:

name: str

age: int

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def make_a_noise(self):

print('grr')Here is a simple example of usage:

cat = Animal('Mixet', 3)

dog = Animal('Blaqui', 3)

cat.make_a_noise() # prints grr

dog.make_a_noise() # prints grrBut maybe, after some time, we want to make the behavior of dogs and cats more realistic: dogs bark making bub, but cats meow making meu. So we could modify the Animal class like this:

class Animal:

name: str

age: int

type: str # cat or dog

def __init__(self, name, age, type):

assert type in ['cat', 'dog']

self.name = name

self.age = age

self.type = type

def make_a_noise(self):

if self.type == 'cat':

print('meu')

else:

print('bub')Well... But when more types of animals are needed, we will have to review the code inside the Animal class again. In this case it is simple enough, but with classes with many more methods, it quickly becomes tedious and repetitive and, therefore, it is easy to miss cases. And nobody wants to read code with so many conditionals.

In these cases, the mechanism of inheritance is the solution. Inheritance is a fundamental concept in object-oriented programming that allows the creation of new classes based on existing classes.

With inheritance, we would start by defining the Animal class as at the beginning:

class Animal:

name: str

age: int

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def make_a_noise(self):

print('grr')and, from it, we would define a new Cat class and a new Dog class:

class Cat(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('meu')

class Dog(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('bub')The syntax class Cat(Animal) and class Dog(Animal) indicates that the Cat and Dog classes inherit from the Animal class. This reflects the fact that cats and dogs are animals. At the Python level, this also means that objects of the Cat class have the same attributes as those of the Animal class, and the same for objects of the Dog class. Therefore, we can do something like

cat = Cat('Mixet', 3)

print(cat.age) # prints 3because every cat (and every dog), by being an animal, has an age attribute and a name attribute.

Now, the definition of the classes has redefined the make_a_noise method, so each object will now make the noise corresponding to its type:

animal = Animal('Campió', 6)

cat = Cat('Mixet', 3)

dog = Dog('Blaqui', 4)

animal.make_a_noise() # grr

cat.make_a_noise() # meu

dog.make_a_noise() # bubNote that, since an object of type Animal has not been specialized, it continues to make grr.

Redefining methods of inherited classes is not mandatory, but when done, the same interface must be respected.

Inherited classes can have new methods, but these are specific to elements of that type. For example, cats can purr, while dogs cannot. Therefore, if we now add the purr method to Cat:

class Cat(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('meu')

def purr(self):

print('ron-ron')we can apply this operation to cats, but not to dogs:

cat = Cat('Mixet', 3)

dog = Dog('Blaqui', 4)

cat.purr() # ron-ron

dog.purr() # ❌ AttributeError: 'Dog' object has no attribute 'purr'Similarly, if we now add a dangerous attribute to the Dog class to indicate whether a dog is potentially dangerous or not:

class Dog(Animal):

dangerous: bool

...we can access this property for dogs, but cats will not have it:

dog = Dog('Blaqui', 4)

cat = Cat('Mixet', 3)

print(dog.dangerous) # prints True or False

print(cat.dangerous) # ❌ AttributeError: 'Cat' object has no attribute 'dangerous'Often, the parent class constructor is reused in the child class constructor. This can be done by explicitly invoking the parent class constructor from the child class constructor via super(). For example, in the Dog class, we can invoke the Animal constructor to initialize the name and age attributes:

class Dog(Animal):

dangerous: bool

def __init__(self, name, age, dangerous):

super().__init__(name, age) # invokes the Animal constructor

self.dangerous = dangerous

def make_a_noise(self):

print('bub')Inheritance thus allows new classes (called child or derived classes) to inherit the attributes and methods of existing classes (called parent, base, or super classes). This implies that child classes can reuse and extend the behavior of parent classes, avoiding code duplication. Moreover, inheritance facilitates hierarchical organization of code, as classes can be grouped into more general categories (parent classes) and more specific categories (child classes). This hierarchical structure improves code understandability and allows changes in parent classes to automatically affect all child classes, promoting consistency and maintainability of the system.

Inheritance and polymorphism

A great advantage of inheritance is that functions can handle objects without knowing exactly their type but invoking the functions that correspond to their type.

To see its usefulness in a concrete example, let's revisit the previous class hierarchy:

class Animal:

def make_a_noise(self):

print('grr')

class Cat(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('meu')

class Dog(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('bub')Suppose we have a function that makes an animal make noise a certain number of times:

def make_many_noises(animal, times):

for _ in range(times):

animal.make_a_noise()In this case, it is obvious that the following code

animal = Animal('Campió', 6)

make_many_noises(animal, 3)will print grr, grr, grr. But what is not so clear is that, since cats and dogs are animals, the make_many_noises function can also be applied to objects of type Cat and Dog! And, moreover, the make_a_noise method invoked by the make_many_noises function corresponds to the object it receives:

cat = Cat('Mixet', 3)

dog = Dog('Blaqui', 4)

make_many_noises(cat, 3) # meu, meu, meu

make_many_noises(dog, 3) # bub, bub, bubThis is great, because although the make_many_noises function was written for animals, its final behavior depends on the type of animal passed as a parameter. Thanks to inheritance, functions can be written that manipulate objects of types whose details are not yet fully known.

This concept is called polymorphism. Polymorphism is the ability of objects of different classes to respond to the same method or message in a unique and consistent way, allowing uniform treatment despite the particular differences of each class.

Note: this behavior can only be performed for derived classes. If we have a function that accepts objects of type Cat, it can assume that cats (and all classes derived from them) have the purr method, but objects of type Dog do not have it and therefore cannot be passed as a parameter. This error can be easily detected with mypy or PyLance: INSERT IMAGE. If type error detection is ignored, this error will manifest at runtime.

Polymorphism works not only with functions but also with methods. For example, if we have an Animal class with a make_a_noise method and a Cat class that redefines this method, we can call make_many_noises on an object of type Cat and the make_a_noise method that will be executed is the one from the Cat class:

class Animal:

def make_a_noise(self):

print('grr')

def make_many_noises(self, times):

for _ in range(times):

self.make_a_noise()

class Cat(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('meu')

class Dog(Animal):

def make_a_noise(self):

print('bub')Indeed:

animal = Animal()

animal.make_many_noises(3) # grr, grr, grr

cat = Cat()

cat.make_many_noises(3) # meu, meu, meu

dog = Dog()

dog.make_many_noises(3) # bub, bub, bubIn fact, polymorphism is not a feature of methods or functions, but of objects.

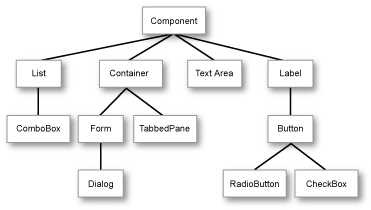

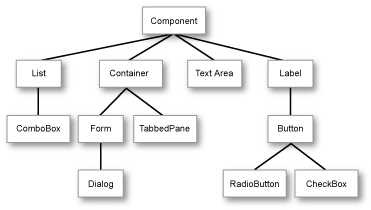

Class hierarchy

It is very common for a base class to give rise to more than one base class. For example, Cat, Dog, and FarmAnimal can derive from Animal. And Cow and Sheep can derive, in turn, from FarmAnimal.

This is usually represented like this:

When using libraries, it is very common to encounter very complex class hierarchies, such as this one for graphical elements of an app:

Application: Geometric shapes

from dataclasses import dataclass

import math

@dataclass

class Point:

"""A point in a 2D space."""

x

y

class Shape:

"""A base class for geometric shapes."""

_name = "shape" # Class attribute for the name of the shape

_center # Center of the shape

def __init__(self, center):

self._center = center

def center(self):

return self._center

def area(self):

return 0.0

def __str__(self):

return f"{self._name} with center ({self._center.x}, {self._center.y})"

class Circle(Shape):

"""A class representing a circle shape."""

_name = "circle"

_radius

def __init__(self, center, radius):

super().__init__(center)

self._radius = radius

def area(self):

return math.pi * (self._radius**2)

def perimeter(self):

return 2 * math.pi * self._radius

class Rectangle(Shape):

_name = "rectangle"

_width

_height

def __init__(self, center, width, height):

super().__init__(center)

self._width = width

self._height = height

def area(self):

return self._width * self._height

def perimeter(self):

return 2 * (self._width + self._height)

if __name__ == "__main__":

s = Shape(Point(0, 0))

c = Circle(Point(1, 1), 5)

r = Rectangle(Point(-1, -1), 4, 6)

print(f"{s} and area {s.area()}")

print(f"{c}, area {c.area()} and perimeter {c.perimeter()}")

print(f"{r}, area {r.area()} and perimeter {r.perimeter()}")Multiple inheritance

Multiple inheritance is a concept in object-oriented programming where a class can inherit attributes and methods from two or more parent classes. This feature allows a new class to obtain characteristics from multiple sources, combining them into a single child class.

An example in Python could be a class that inherits from two different parent classes:

class Shape:

...

class Color:

...

class FilledShape(Shape, Color):

...In this example, the FilledShape class inherits from both the Shape class and the Color class. This means that a filled shape created with this class can access the methods of shapes and the methods of colors. Likewise, a FilledShape can be passed as an actual parameter to any function that receives a formal parameter of type Shape and to any function that receives a formal parameter of type Color.

Multiple inheritance is an advanced topic: The dangers of multiple inheritance include complexity and difficulty in maintaining code, as multiple sources of behavior could collide or cause conflicts. Moreover, it can lead to excessive dependency between classes, making future modifications difficult and reducing system flexibility. The multiple inheritance hierarchy can also cause readability and comprehension problems, especially in large projects.